Max DiCorcia, “You are My Friend”

December 5, 2016

An Oral History with David Yarritu 11/14/2016

by Svetlana Kitto

I had been in New York for about a year when I met Max. He was my boyfriend for four years, from 1984–’88, when he died of AIDS. Max DiCorcia. He totally changed my life.

The first time I ever saw Max was on East 7th Street, between 1st and 2nd, in front of Middle Collegiate Church. It was at a fashion show for Andre Walker; I went because a friend of mine was modeling. After the show, I was out on the steps with Tabboo!, Jimmy [Paul], and Hapi Phace, and Max came up and started chatting with them. It was love at first sight! I was like, who the hell is that? I grilled Tabboo! and Jimmy about him and of course they were being very withholding. Everyone was in love with Max.

A couple of days after New Year’s, 1984, I showed up at The Pyramid. There were very few people there because most people are too hungover after New Year’s to go clubbing. But there was Max. I started doing that whole dance of coyly moving towards him; dance a little closer; a little bit closer. I showed up next to him and started dancing with him. He was into it. I invited him back to the place I was crashing at on MacDougal Street. I had the whole place to myself because my friends from Texas were gone for the holidays. We made out. It was really intense and before it went further, he decided to go home. “But I want to see you again,” he said. It left me with stars in my eyes.

I went to his place a few nights later. It was a little house in the back of a tenement on Avenue B. A really unique little thing, with a fireplace and a skylight. That night we had a heart-to-heart. He explained to me that he was sober, in a 12-step program, and that he was HIV positive. And that he was one of the first 100 people in New York to be diagnosed with HIV. Up until that point, I’d never met anyone who was sober or HIV positive. It immediately woke me up. I was really impressed with his honesty and curious about his sobriety.

One of his ways of dealing with his diagnosis, at a time when there was no cure, was to turn to alternative medicine and macrobiotics—the healing arts. He told me a story that when he was a teen in Hartford, he had checked out a book at the library about a woman who cured herself of brain cancer with macrobiotics. He really believed he could cure himself of HIV. I believed him too.

Soon after we started seeing each other, I had to leave for England to go be a pop star with ABC. Max decided he would come and spend the summer in Europe. He got a scholarship to a macrobiotic cooking school in Switzerland. It was so magical, very Sound of Music, and Max rented this little Swiss chalet with geranium flower boxes.

At the end of the summer he went back to New York and I stayed in England. Communication involved mail and long phone calls that cost a lot of money. I came to a point in my relationship with ABC where I decided I wanted to try something else. So I left the band and came back to the US in early ’86.

When I came back to New York, Max told me that if we were going to make a go of our relationship I was going to have to become macrobiotic and get into a 12-step program. I jumped right in. I had the luxury of having some money from being in the band so I spent all my days shopping for brown rice and organic vegetables (which were really hard to find back then!). I didn’t have to work. Soaking beans. Cleaning rice. Pickling things. It’s a lot of work to be macro in the true sense.

Before Max my relationships were pretty superficial. Max was a real catalyst of change for the way I approached my whole life.

He managed to stay alive for five years, which was a really long time in those days. He had been doing really well with his practices but then he developed pneumonia and had to be hospitalized. That was really scary because he had convinced everyone he was going to cure himself with macrobiotics. I remember when he was in the hospital his family came from Connecticut and they were really freaked out because nobody knew if he was contagious. Everyone was standing back like five feet—I just decided to climb up on the bed and sit next to him. I was so in love with Max I really didn’t care.

He got out of the hospital and he developed other problems like Kaposi sarcoma. Many men with AIDS developed it. He had lesions on his legs. Then he developed dementia which was really hard—there’s no guidebook on how to deal with that. Then he lost his little house on Avenue B and had to move in with his older brother P.L. [Philip-Lorca diCorcia [1]], in Tribeca. He never felt comfortable there because it wasn’t his place. I think he felt more and more defeated; that he didn’t have a home, that he wasn’t able to get a new home, that his dream of curing himself with macro and shiatsu wasn’t coming to pass. At a certain point he decided to move back to Hartford with his mom and sisters and brother. They took care of him. He was trying to spare me I think. Like if he could go and disappear it would be less painful for me. He would come back to New York occasionally. He started this whole campaign of “you need to start looking for another boyfriend.” I was in a lot of denial.

A Silent Auction of Artists’ Bird Cages to Benefit Max at the Pyramid Club. Invitation, March 1988. Courtesy of David Yarritu.

At one point Max needed money for his healthcare and so he organized a benefit where he asked different artist friends to adorn these birdcages he had gathered from thrift stores and junk markets. David Wojnarowicz, William Wegman, Greer Lankton, Simon Doonan. Tom Rubnitz bought the one that I did. The Wojnarowicz one was bought by one of the founders of Paper magazine. Bergdorf-Goodman bought one and it was displayed in a window on Fifth Avenue.

A Ball for All Birds to Benefit Max at the Pyramid Club. Invitation, March 1988. Courtesy of David Yarritu.

The night of the birdcage auction there was also a ball—I think Max designed this invitation. It was a lot of really cool people. The ten-dollar admission to the Pyramid ball went to helping pay for Max’s medical expenses. This was in March of 1988. He died in October 1988.

It was his brother P.L. who called to tell me that he had died in Connecticut. I was so angry—really angry, devastated. I felt abandoned and crushed that Max wasn’t able to cure himself. I still thought he would convalesce in Connecticut. We had a memorial service for him there, and his remains were cremated. It was very strange, they had a service out in a park, or I think actually it was the cemetery where his father was buried, and it was raining. I brought a boombox and played some gospel music because Max loved that. We went back to his sister’s house for food and drink and while we were there the postman arrived and it was Max’s ashes. It was so spooky, like he showed up for his own party. They put the box of his ashes up on the mantel.

I organized another memorial back in New York for all of his friends there. I wanted to give him this ridiculously lavish memorial. We rented the Quaker Meeting House on Stuyvesant Park. I enlisted the Lavender Light gospel choir. We ran the memorial sort of like an AA meeting or a Quaker service: anyone who felt moved to speak could share. We just stayed there as long as people needed to. There was a lot of laughter and a lot of tears.

There were two invitations to the memorial. One that they passed out at AA meetings. And I commissioned Tabboo! to do this other one, sort of like a holy card to keep in remembrance. On the border it says “fashion genius,” “cook,” “florist,” “swimmer,” “dancer.” He was a great dancer.

Here, you see? There’s a line at the bottom that says: Please go to The Pyramid.

This is the invitation to The Pyramid; it lists people who were performing. I do remember Lady Bunny lipsynched “You are My Friend” by Patti LaBelle—not a dry eye in the house. And I performed “True Blue” by Madonna because Max loved her.

I haven’t looked at this stuff in a long time. It’s been in a box. But looking at it now I’m impressed by it. I tried to do the best I could for him. He deserved everything.

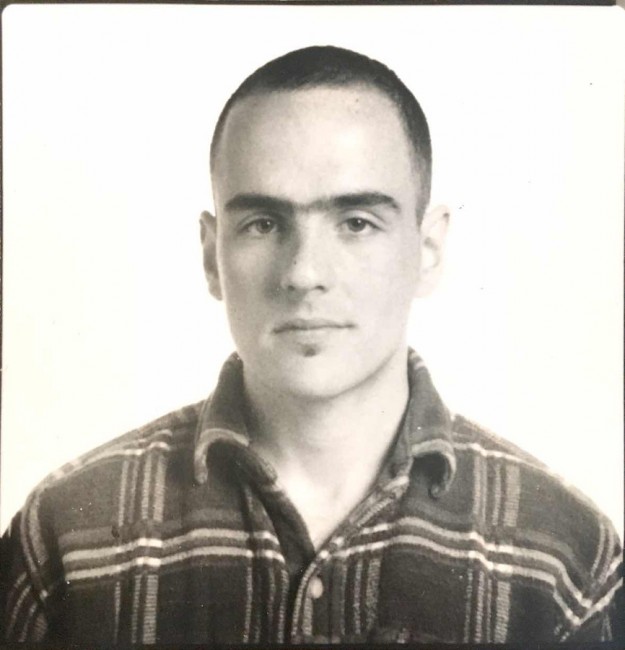

This picture is by P.L. DiCorcia, who is a very well-known artist and photographer. I was looking at the contact sheets and said to Max: “I’m gonna take this, it’s such a good picture of you.”

I wish I had taken more pictures of Max.

[1] Three photographs by Philip-Lorca diCorcia, including one of Max, were included in the pivotal 1989 Artist Space exhibition Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, curated by Nan Goldin. Nan Goldin’s introduction to the exhibition is reprinted in the Danspace Project Platform 2016: Lost and Found catalogue. [JSC]

As part of our online Journal, Danspace Project has invited artists, curators, scholars, historians and others in our community to contribute entries as Writers in Residence and guest Respondents. Each contributor has been offered an open invitation to respond to work presented by Danspace Project; writings gathered here do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of Danspace Project, its artists, staff, or Board of Directors.