Moving Through: 10 Years of Danspace Platforms by Maura Nguyen Donohue

May 10, 2021

Maura Nguyen Donohue is the Writer-in-Residence for Platform 2021: The Dream of the Audience.

Donohue conducted extensive research in 2019-2020 around the history of the Platform series, cataloguing the many curators, curatorial fellows, writers-in-residence, performances, print publications, and the Journal issues that made up the past 10 years of Platforms. She interviewed past curators, collected their reflections, and spent slow time recalling her own memories and values as a long-time Platform audience member.

Please read or listen to her essay, “Moving Through: 10 Years of Danspace Platforms,” below.

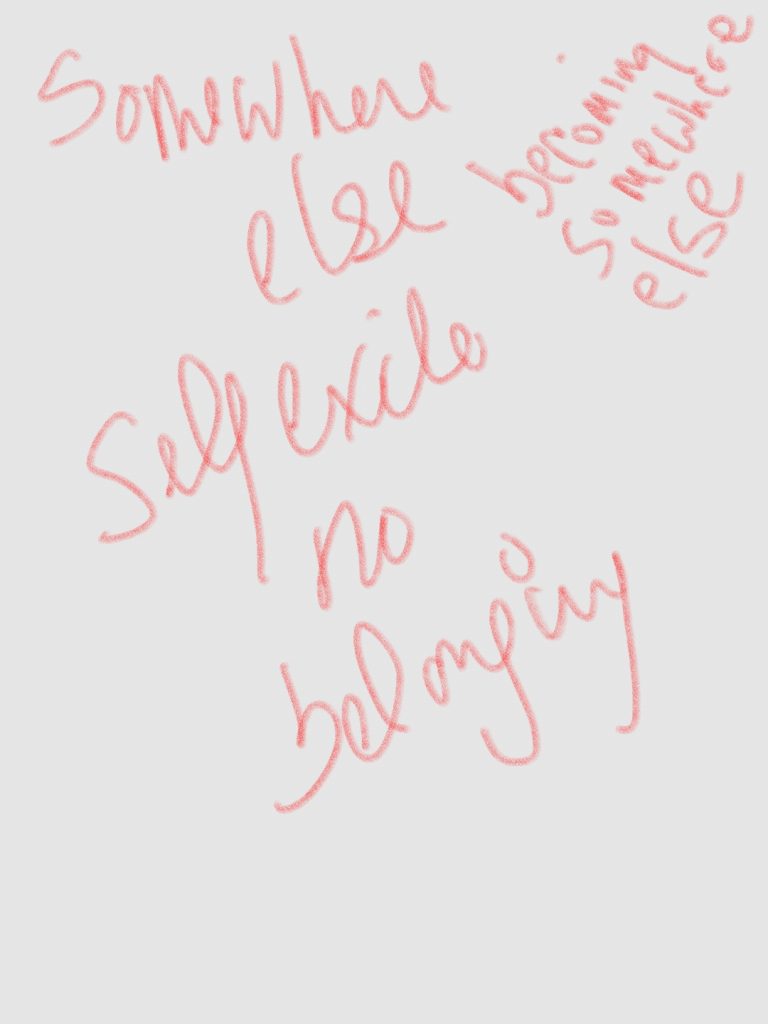

…maybe it’s not so much about being recognized as who we are as it is about staying together, feeding each other, knowing where we are, and moving through.

– Alexis Pauline Gumbs

Who cares?

In the Fall of 2016, during Danspace Project’s Lost & Found Platform, curator Ali Rosa-Salas, noted during a public discussion that the etymology of the word “curator” includes an expected duty “to care,” as it comes from the latin curare, meaning to care for or attend to. An MA candidate at the Institute for Curatorial Practice in Performance (ICPP) at Wesleyan University, at the time, Ali was offering a concept that Danspace’s Executive Director and Chief Curator, Judy Hussie-Taylor (a co-founder of ICPP) had helped bring to the fore through her Danspace Project seminal PLATFORM initiative. The Platform series was launched in 2010 as a new presenting format using five basic design components: each Platform would have a guest artist as curator; a print publication; a guest editor; commissioned public performances; and creative contexts to illuminate artistic or curatorial thinking. Informed by the choreographic structures, improvisational scores, and artistic processes of her dance artist friends and contemporaries, Judy had challenged the status quo of the performance presentation world that she encountered in New York.

If curation at Danspace is imbued with an etymological integrity of caring, the particularity of curation for Danspace Platforms has revealed an even more radical practice of attending that poet (and self-defined Black Troublemaker) Alexis Pauline Gumbs calls “schooling” in her meditation, Undrowned. Observing natural collaborations of dolphins, she asks “What if school, as we use it on a daily basis, signaled not the name of a process or institution through which we could be indoctrinated, not a structure through which social capital was grasped and policed, but something more organic, like a scale of care. What if school was the scale at which we could care for each other and move together?”[1] To be in school is to concern ourselves with current urgencies without erasing pasts or inventing futures. It asks us to increase our response-ability, so that caregiving, caretaking, caremaking are not obligatory labors of love but the most basic and essential skills for our multi-special survival on Earth.

Every Platform becomes a school. Platforms bring cooperative structures into insistent formation. The guest artist curators enter a wit(h)nessing process of merging long conversations with Judy, artists, staff, scholars, designers and others (sometimes over years) into meaningful convergences. No one curates a Platform alone. Platforms create kin as each group forges a unique navigational language as if “knowing who they’re with helps them know where they’re at and where they want to be.” [2] Audiences join the school of artists and others, as the option to engage with individual works as part of a larger system of ideas disrupts the isolating culture of industrial model presentational structures. In a resistance to the gatekeeper or tastemaker hierarchies and histories, Platforms gather around lines of inquiry with a multiplicity of perspectives and formats, flowing in real, quantum, and abstracted time. We swim each sea together.

“Places like Danspace only exist and exist as long as they do because of their connectedness to community and not just the art-making but the survival of the community or the memorial [in] all these other ways in which… it becomes something greater than the good shows… It’s like a life to Lifeline.” – Will Rawls (co-curator, PLATFORM 2016: Lost & Found)

Like choreographic processes, the meaning is made in connections. In Staying with the Trouble, author Donna Haraway instructs us with the task to “make kin in lines of inventive connection as a practice of learning to live and die well with each other in a thick present.”[3] Looking back on 10 years we can glimpse complex connectivities spreading back and forth within a continuum of mutual growth. We wit(h)nessed ourselves repeatedly becoming “fully present, not as a vanishing pivot between awful or Edenic pasts and apocalyptic or salvific futures, but as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings.”[4] places, times, matters, and meanings could easily have been the title for many a Platform, oddkin to Judy’s nascent Platform conceiving conversations with the first guest artist-curators, Trajal Harrell, Ralph Lemon, Juliette Mapp, and Melinda Ring about “slippery relationships to time, history and architecture.”[5] Pressing upon the absence of contextual discourse in the one-week presentational model, additional guest curators David Parker, Ishmael Houston-Jones, DD Dorvillier, Lydia Bell, Eiko Otake, Will Rawls, Jenn Joy, Claudia La Rocco, Reggie Wilson and Okwui Okpokwasili also pushed these ideas inward and outward, effectively worlding new realms and paradigms alongside Judy and the Danspace Project staff.

“The coming together lends itself to the fleeting reality of each Platform’s universe. A world is built, a system and universe… Platforms are the moments in time when all that is Danspace Project comes into full spotlight exposing the artists, curators and Danspace Project’s processes all together. Groups bond with one to the other as they become teams of experience…[the] process of creating sometimes has the reputation that it isolates. The Danspace practice of Platforms flies in the face of this potential isolating.” – Reggie Wilson (Curator, PLATFORM 2018: Dancing Platform Praying Grounds: Blackness, Churches, and Downtown Dance)

In reading reflections from the curators, I found time collapsing like a cinematic hyperlapse shot. Constellations illuminate themselves, perceived lines align distal bodies with one another into apparently logical formations. As past, present, and future liven and intermingle, the cosmology of solitary systems disintegrate. We glimpse a whole, a universe of interconnectedness that transcends chronos. “Nothing is connected to everything; everything is connected to something.”[6] Observing the platforms from a distance is akin to gazing into the night sky watching in our real time a current event from long past chaos. There is some thought that what was being made in that particular today had origins in earlier explorations while living within this now and offering the vanguard where evanescent formations of live bodies mattered.

The Platforms have held vigil over substantial global changes and each curation has heeded the potency of creation and re-creations in mending, or at least tending, historic rifts. During the 2016 Lost & Found Conversation Without Walls panel “FOUND: Feminism, AIDS, and History,” artist Heidi Dorow stated that we’re all seeking our own “networks of kinship.” And on that bright October afternoon and many other times in and around St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, dance-kin have worked the net, loosening lonely knots, into webs of remembrance, gratitude and fellowship. Even now, amidst the most historic upheaval for just about any sentient human, I’m still submerged in the tent, swimming in the shared songs of Okwui Okpokwasili’s interrupted 2020 Utterances From The Chorus Platform. I’m catching Cecilia Vicuña’s breath as we pass it among everyone in the room, I’m waiting to eat with my hands from the same Spiral Theory Test Kitchen table as the rest of a very large pod. I’m sitting (naively, slightly anxiously) in a full house watching Peggy Cheng, one of my oldest friends, dance in the last show I saw live [7] and in person before the world shut down in March 2020.

“I continue to say ‘Distance is malleable,’ and ‘I want to maximize the potentials of selected encounters,’ … I continue to dance my duets with living and dead, because both living and dying take a long time.” – Eiko Otake (Curator, PLATFORM 2016: A Body in Places)

What does it mean to care? Inaugural Platform guest artist-curator, Ralph Lemon described “a moment of absolute gift exchange.” In this reciprocity of generosity, the wit(h)nessing of non-transactional gifting offers a new faith. What could it mean as humans to not succumb to “abstract futurism and its affects of sublime despair and its politics of sublime indifference.”[8] If data and recent lived experiences give us a ‘game over’ scenario, why bother attending to art making, why advocate for culture, why fight for it, why want, why worry, why work? 2011 -2014 Conversation Without Walls curator Jenn Joy states at the beginning of The Choreographic, “To engage choreographically is to position oneself in relation to another.”[9] The Platforms remind us that in dance, we are more than the sum of our produced and public works. In dance, we are intrinsically embodied and bound as humans to other humans in a world built (and destroyed) by humans. In dance, the relationships built through the work is what matters over time. The pod cares for the entirety, resists mythological narratives of rugged individualism. In dance, we remember another existence, other ways of being.

“Choreographic presence, circumpolar hold, deep listening, coordination. Call back the school that fear untaught me. Give me the heartbeat I remember. Call it love.”[10] With Platforms, Judy Hussie-Taylor has spun a web that has schooled our field. It has expanded the relevance of contemporary performance by situating it at intersections of practice, politics, presentation, history, site, community, joy, conversation, bodies, words, memories, fantasies, scholarship, and silliness. She calls it “relational curating,”[11] I call this love too. In the school that reclaims what “fear untaught me,” I could roll in a sparkly leotard on the floor in a Miguel Gutierrez Death Electric Emo Protest (DEEP) Aerobics makeout moment or Cori Olinghouse could line up deconstructed vaudeville with voguing and light up the place when Archie Burnett, Javier Ninja and the House of Ninja came to the church and burned it down[12] during the 2011 Body Madness Platform. I could doze during a 24-hour vigil for the Fukushima disaster in the 2016 Platform, A Body in Places or weep, kneeling at a Lost & Found Memory Palace scroll later that year. I could wander delightedly into a David Zambrano “Soul Project” Solo in the formative 2010 Platform curated by Lemon, i get lost.

Let’s get lost together, again. Reflecting in the oceanic wake of radical caring demonstrated over nearly a decade by over a dozen curators, writers, curatorial fellows, research fellows, artists, panelists, scholars, staff, and audiences—one cannot help but consider the countless ripples that have spread out from this little corner of 10th and 2nd in the eastern village of the isle of Manhattan, on the Lenape island of Manhahtaan (Mannahatta), during an early decade within the new millennium. As an especially dire epoch unfolds around us, acute care seems the only manageable treatment against the chronic ache of contemporary existence on this planet as we learn to stay in the schooling, “in a curriculum called ‘how we endure’.”[13]