Fugitive Memories: A Fiction by Emmanuel Iduma

November 25, 2020

“Fugitive Memories: A Fiction” is an essay by Emmanuel Iduma commissioned by Danspace Project and first published in the catalogue for PLATFORM 2015: Dancers, Buildings, and People in the Streets, guest curated by Claudia La Rocco.

“I will write about my time in New York while I write about wanting to write a novel on dance and travel. Memory has a place in the past as well as in the future, and when we enter a contract to remember we float as fugitives. Maybe this entire thing rests on a hallucination.”—Emmanuel Iduma

Often guided by the words of James Baldwin and through a speculative gaze on memories both personal and historic, Iduma encounters Lynn Tillman, the Grand Union, The Natural History of the American Dancer, and a performance-artist-couple making plans to walk across the whole of Nigeria.

I want to think I am excavating a piece of timely garbage.

Is this what the writing is? Stupid code into which history doesn’t quite fit, fraught with the uncertainty of its own existence, frustrated by the demand that it should conform to meritocratic behavior; it is helpless when it fails to survive by nonconformity, as though the very idea of nonconformity is a half-assed attempt at defiance; and we know that any writing about the past is truly half-assed, shaken by the vulnerability of memory, the illusions that have swapped places with reality, as though the world of fact is commandeered to berate and underrate itself; and maybe really we have to accept that exaggerated stories are in perfect shape, as they become a version of truth that isn’t subjected to trust or to a promise of certitude; and we equally know of course that as Walter Benjamin says “death is the sanction of everything the storyteller can tell” and that the storyteller “has borrowed his authority from death,” so that any history we retell essentially accounts for its own burying, for its own cremation, and fizzling, unimportance, and decay; and we are also certain that unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and withers, it remains without promise of becoming a large crop; so we take a body of history as though bound to the idea of a Eucharist communion, and we break it into many halves, eating and drinking in remembrance of a moment of beauty and togetherness; for certainly the writing exists as this breaking apart, this tearing open— with its disturbing materiality and physicality we know it suggests many ambivalent selves, because one self is trying to out-write the other; it is the attempt to call a morsel of bread a piece of shit, and vice versa—I remember Clarice Lispector’s narrator in The Hour of the Star, who refuses to write the girl’s story in a way that transforms words into gold, words originally intended for bread, so that the child dies of hunger—because writing is, in a sense, feeding; and we turn to the writing of any history to lessen the pangs of hunger, with the knowledge that passing time gives us a gluttonous appetite for nostalgia, for we have to relish our insatiability; and also our incurability—once facts are distorted in the telling of a story we might be tempted to rail against falsehood, but I realize that within those falsehoods there is the potential for the glimmer of grace, by which I mean mischief and certainly humor; take the example we find in István Deák’s Weimar Germany’s Left-Wing Intellectuals: A Political History of the Weltbühne and Its Circle: “Because of an early spelling mistake, the masthead of the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung was printed with a spelling error all through the fifty years of its existence”; all this leading me to suggest a sort of ethics for calling up the past, because I always think of historical codes that wouldn’t fit the purposes of the ideal, and memories that transgress our well-behaved present, and compromises that we cannot envision from our positions of deterministic clarity—a notable example being the story of a captain of a slave ship recounted by C.L.R James in The Black Jacobins: “Outside in the harbor, waiting to empty the ‘trunks’ as they filled, was the captain of the slave-ship, with so clear a conscience that one of them, in the intervals of waiting to enrich British capitalism with the profits of another valuable cargo, enriched British religion by composing the hymn “How Sweet the Name of Jesus sounds!”

Lagos in the early seventies when I left Nigeria was rife with Fela’s exuberance; in addition to juju music, the resultant parties, and in sum the rise of a flamboyant upper class enriched by the widening government coffers. I turned to dance because I felt I had to watch the liberated motions of movement. I didn’t think people on the street offered this; once or twice a week I walked from Harlem to Washington Heights and back at a slow pace to watch moving people. Each time I returned heavy with discontent.

Perhaps I was first fascinated by dance because of a photograph of a dancing couple. The photograph was the image on a postcard my father had returned with from Bamako. It had been taken in 1963, by a photographer who I now forget—although I guess it was by Malick Sidibé. The couple, as it seemed, were abandoned to their motions. It was happiness of a strange sort, simple and surreal. The postcard became talismanic. I clung to it with the hopes of reenacting the couple’s vivacity, or as a way to recognize it when I watched other enactments. Dance, in my understanding at the time, was a form of protest against the body’s inclination to stay composed. I write bearing in mind the first sentence of a James Baldwin essay: “I will let the date stand, but it is a false date.” In no time we realize that the dates we have been given are both constructed and colonized; in essence we were educated with the Occident’s curriculum and since then our time is warped by our struggle to escape the consequences of being named by others. I have always borne the burden of being named—in the mid-seventies when I arrived to study in New York, and today still, when I am not Nigerian enough for my friends because I speak little Igbo and my pidgin English, they say, sounds rehearsed—of course an improbable “today,” a falsified yesterday. In the stretch of decades between then and now, I am left with disparate incidents around dance that I have been made to account for. At first I thought I must address a fictional “you” that is also “I,” yet as the process began I turned my “I” into a pointing finger, protected by the distance between a first and second person, and disillusioned to realize that recollection is a deeply personal act—NO “YOU” ALLOWED.

“From the margins,” Lynne Tillman wrote, “I’m supposed to speak as a native informant.” I knew from the earliest moment of my arrival that I was to stew in the muck of marginality. Mired and undeliverable, sinking, breathless, entangled—these emotions have no end. First it was a question of recognizing myself as black, and then lacking sufficient knowledge of blackness to be black enough, and finally realizing that neither the knowledge of blackness nor the feeling of blackness mattered—only the fact that then, as today, blackness often meant disposability. In another sense I was a Nigerian graduate student in the early seventies, a carrier of privilege; a year after Nigeria’s civil war when I arrived, studying in America was impossible for many to imagine or afford. In ways I cannot remember my privilege seemed to conflict with realizing that in America I existed on the margins. I possessed the sort of body that had been traded at auction-blocks.

The Baldwin essay I mentioned earlier is from 1979; it’s a review of Lincoln Collier’s The Making of Jazz, but also a meditation on black history, music and enslavement. In the essay there are certain declarations that oscillate between rage and certainty, despair and prescience. One such is this:

“This music begins on the auction-block. Now, whoever is unable to face this – the auction-block; whoever cannot see that the auction-block is the demolition accomplished, furthermore, at that hour of the world’s history, in the name of civilization: whoever pretends that the slave mother does not weep, until this hour, for her slaughtered son, that the son does not weep for his slaughtered father: or whoever pretends that the white father did not– literally, and knowing what he was doing – hang, and burn, and castrate, his black son: whoever cannot face this can never pay the price for the beat which is the key to music, and the key to life.

Music is our witness, and our ally. The beat is the confession which recognizes, changes and conquers time. Then, history becomes a garment we can wear, and share, and not a cloak in which to hide: and time becomes a friend.”

I told my friend Amil this was all I had meant to say about his growing interest in ethnomusicology. I wouldn’t think for him—or for Baldwin for that matter—but it seemed clear to me that it was clear to all of us that we couldn’t talk about the history of our blackness without the music that was produced in our captivity. Our task always, I said, reiterating Baldwin, is to pay the price of this captivity—to turn anguish into rhythm—in our music, our dance, our writing. Amil agreed: “As an essayist and novelist, Baldwin used the fire of the sermon, which I understand as a musical fire.”

But we are not always clear about the history handed to us. These are histories shaped by fogginess. Each time we begin to deal with history we’re dealing with what is said to be provable, ascertainable, or sometimes true; and it seems to me that there are certain factoids that cling to us, my father’s brother who disappeared during the Biafran war and hasn’t been seen since then, and no one knows if he survived the war. These are personal histories, but in time they become speculative. They bend to the necessities of our imaginations, or morph according to the gestures of our desires. When these histories morph it becomes useless for us to think of them as history. It is very courageous to attempt to think of history this way. This courage will be found in the making of art, in music that sounds like a mellow epiphany, in music to be found in the voices and trumpets and falsettos of dead people “more vivid that what’s called history,” which is what Baldwin calls them—King Oliver, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, John Coltrane, Jelly Roll Morton, The Duke, Charlie Parker, Nina Simone, Mme Mary Lou Williams, Carmen McRae, The Count— voices and trumpets and falsettos that ring on today.

I have started thinking of writing a novel, but I fear I would rehash moments and incidents from books that have shaped my thinking, that there isn’t anything primal and original to say, and even when I’ve figured out a plot I fear I won’t find a form, a shape, a manner of telling, in sum I won’t find a way to berate time—for Breyten Breytenbach tells us “time is not always of the same intensity – in the novel, as in life, there will be times of forgetting.” I cannot bring myself to tell an elliptical story, conscious of what might be omitted, the roundedness of a character’s life that might seem like a square; of course I began to have these thoughts when I read an incident in László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below—Susan Sontag very aptly described László as “the Hungarian master of the apocalypse”—and the incident is one where a man visiting Athens goes to see the Acropolis: “he then understood,” we are told, “that what he had come here for would remain forever unseen by him: not only, he thought bitterly, not only would he never know the scale of the dimensions of the Acropolis, but he was never even going to see the Acropolis, even though he was here at the Acropolis…”; so we see a man who has desired throughout his life to know the scale of the dimensions of a masterpiece, and his desire is grounded in all the stories that have been told about this masterpiece, in other words he has accepted wholesale the constructions of history, and now that he goes to see what he has been told about, he discovers he cannot bear to look at it. The sun is blinding and he is weak.

Yet I remember walking into a Grand Union performance. David Gordon would say later that every group needs a very intelligent madman, that he was perhaps the madman in that group. What I saw that evening were disparate vanishing points; a craziness that made me feel the opening of all my veins. I stood with pocketed hands, and my eyes were fixed but roving. The room was hardly full, about a dozen or two-dozen people. For a minute I thought my distinguishable blackness would bring the performance to a close. I became aware that it wasn’t about openings or finales, but the irretrievability of an instant. This scared and shook me. My life was immediately halved: knowledge about movement that existed before that performance, and knowledge about movement that I began to have. What was painfully obvious was the realization—and I felt this as part of the initial rush of emotion—that I needed to develop the language for calling improvisational dance by its proper name.

I began to make frequent visits to 112 Greene Street. It was at 112 that someone quoted Yvonne Rainer before the start of a performance, and I remember pulling out a notebook: “One must take a chance on the fitness of one’s own instincts.”

This prescription was a guide for me when I watched performances by The Natural History of the American Dancer. Most of their material depended on their audiences—so I always felt it evolved as my experience of it evolved. To test the fitness of my instincts, I consistently tried to foresee the next movement in a performance. The fact that I would often be correct surprised me; once I asked Rachel Wood afterwards, “how did you know what I was thinking?”

Or was it Barbara Dilley? I was participating in a world that I presumed had no knowledge of my existence. Being Nigerian was indistinguishable from being black, but I wasn’t raised with the consciousness that blackness was inhibitive. I walked around New York with a naïve swagger, attending performances alongside white-only audiences. The stares I received mattered little to me. Sometimes I berated the unauthorization I felt each time I wanted to participate during, or speak after, a performance. I remember particularly a contact improvisation concert at The Kitchen in 1977. Toward the end, the performers asked the audience for questions which they would answer as they danced. Someone asked about talking while dancing, what it meant. The answer was something like, it is like dancing with a mask. I spoke up next. “What do you do with sexual feelings when you’re dancing?” Stark Smith, I think, replied, “use them.” “For what?” I asked. The reply was, “to keep dancing.” There were calls from the audience.

A couple begins to think of walking across Nigeria by foot, because they have overhead someone read out a passage from a book of aphorisms that’s a joke, which goes something like “it is not because they say the world is small that you think you can walk from Lagos to Accra,” and so these two people who are also performance artists decide that as a disruptive gesture they will walk across Nigeria, disruptive because it will also be a response to Wole Soyinka, who in the early 1960s drove through Nigeria to learn about his newly independent country, and now their walk will re-track Soyinka’s road trip, and what they want to do while on this walk is to dance in public spaces, without invitation or trepidation, knowing of course that they were trained at a circus school in Charlon-Champagne, only freshly graduated, so their sensibilities would have a European bent; but more importantly what would their walk and performances mean now that Nigeria is being torn by religious fundamentalists, and how their performance walk would respond to the collectivist yearnings of Soyinka who insisted in the sixties on true confederacy? With this it is clear that I am setting myself up for a novel that might be irredeemably unreadable, wounded by the disruptions it intends to make, a vague response to history’s importance to the present: yet this is where the contraries threaten to whirl apart gracefully, because a novel is a novel if it is mudded up by time, which is sometimes called plot, or chronology, or chronicle, or even catharsis—and this grace perhaps will occur when the man and woman are dancing on the street, ennobled by halos of spontaneity, surrounded in equal measure by people and buildings, each conferring its own temper upon their movement, because they’ll carry no boom box, investing instead in silence and the sounds of happenstance; because they’ll reread Denby, and quote him to themselves—for instance they’ll say, “At a show you can tell perfectly well when it is happening to you, this experience of an enlarged view of what is really so and true, or when it isn’t happening to you,” believing there is an energy they could emit for the benefit of their audiences.

I will write about my time in New York while I write about wanting to write a novel on dance and travel. Memory has a place in the past as well as in the future, and when we enter a contract to remember we float as fugitives. Maybe this entire thing rests on a hallucination.

This novel, will it be written in present or past tense: if the former, will it fail to reflect on the experience the couple are having, only remaining faithful to recounting their occurrences on-the-go; and if the latter, will it stagger under the weight of reflection, seeming more like an essay (“an ordinary communication”) than a work of fiction (“heightened language”)—and here I am quoting Breytenbach again—or will it become an object where both forms shape, inform, deform, deflate, and imitate each other?

The final sentence of my first novel is “the only thing left to do was to remember.” It’s the story of Ella, a university dropout who is promised fortune and freedom by her brother-in-law, an aide-de-camp to a Nigerian military president, who directly supervises the employment and firing of the president’s mistresses. Ella is with the president, halfway through sex, when he has a seizure and dies. The experience scars her. Her remembrance of the event is a mix of fact and mythology—to deal with her devastation she mythologizes the past, creating a version of who the president was and who he wasn’t. She constantly devalues her experiences, mocking anyone who demanded a chronological recollection of her ordeals. She’s being treated by a psychology professor, who is impatient and constantly bares his vulnerability. One day she disappears without trace.

In the days leading to writing these notes, I typed out Lynne Tillman’s essay in The Downtown Book: The New York Art Scene 1974-1984, sending it out to a reading group. We were bound together by an interest in examining a “shared space between fiction and visual art.” I wanted to know, I wrote to them, if any of them had returned “to familiar places, ideas, and beliefs, with enthusiasm, naiveté, and in paroxysms.” One response was that we would be misguided to think that it was possible to know and articulate those moments of return. Tillman’s point, the respondent said, by using the metaphor of a paroxysm, was to emphasize that history would be repeated because it is elusive. A second respondent who knew about my time in New York pointed out that my version of 112 Greene Street, for instance, was an exaggeration that served any use to which I could put it. “Also, the power of your testimony,” she wrote, “lies in its irrelevance, and any attempt to tell it is a disservice to the history you think you’re protecting.” But I have no history to protect, I replied. In response she asked, “Why then do you remember it?”

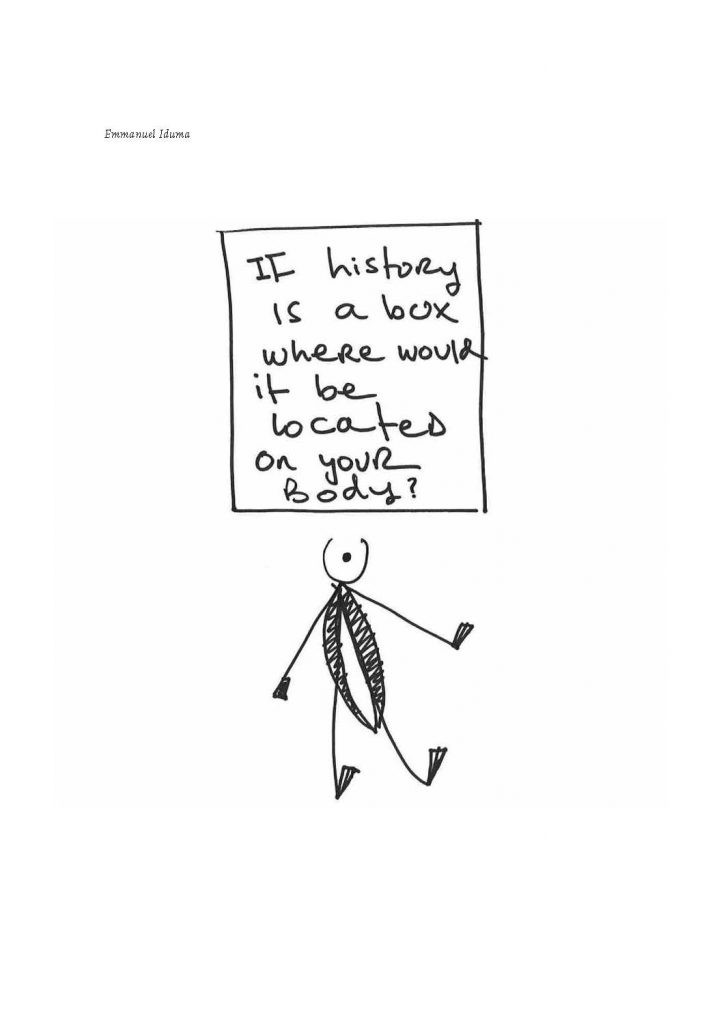

From “Fugitive Memories”, PLATFORM 2015: Dancers, Buildings and People in the Streets. Drawing by Emmanuel Iduma.