“Dance Gravities”

March 4, 2015

1

Fingers inclined skyward remind me of a certain woman who attends church services without fail. In the course of our singing I notice how her hands move to depict the words. Her wrists control gravity. Her palms are cupped like a bowl filled with raisins, or clenched like orange roses. I imagine this as the vernacular of a translator who gives gestures to unhearing worshippers. Yet she faces the altar where melody blends. She sits in the second row. I don’t think she’s deaf. I don’t think she’s dumb. Is there an invisible addressee?

Has she ever been deaf? I resolve to speak with her about this. I imagine her as the recipient of a miracle. For years after her birth she stumbled in the mire of speechlessness until a moment of divine intervention. Have her hands acquired reflexive use in the time following her healing?

This is what I want to ask her.

Then show her screenshots.

Then read her a poem.

My gift is poor, my voice is not loud,

And yet I live – and on this earth

My being has meaning for someone;

My distant heir shall find it

In my verses; how do I know? My soul

And his shall find a common bond,

As I have found a friend in my generation,

I will find a reader in posterity. [1]

2

A prisoner stood face to face with his captor. Their conversation ended as follows: “How can you be a prisoner when we have no record of you? Do you think we don’t keep records? We have no record of you. So you must be a free man.” [2]

3

History takes its own prisoners. There are prisoners who can only become free once they manage to discredit the memory of an event they witnessed. Yet they won’t. The memory of seeing a transcendental ballet could be tagged to your memory like a leech.

A man in Kaitlyn Gilliland’s Serenade workshop said: “I saw it first in 1978.” A woman sitting behind him: “I saw it first 45 years ago.” Then they wondered aloud about the preservation of Mr. Balanchine’s work. They sounded suspicious of a post-Balanchine NYCB (they kept calling him “mister.”) They might have come to the workshop as gatekeepers of a repertoire. Who knows?

The word prisoner is a harsh one. Yet one of the most graceful photographs of Nelson Mandela is one where he poses as a prisoner. If history claims you unyieldingly, let no one think you gave in without a fight.

4

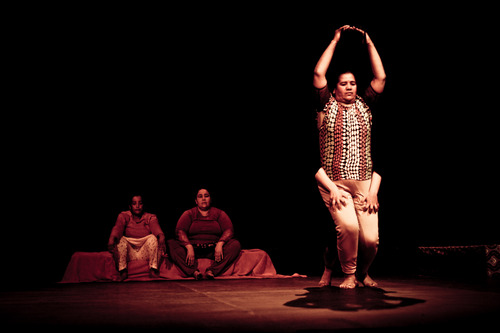

Gilliland tells us that the most iconic moments in Serenade are the most precarious. Precarious is formed from Latin precari, to pray. People sometimes pray when things are held in balance—impending doom, possible devastation, looming failure. I have seen footages of ballerinas held up by their waists. For the uninitiated the movement upward is glorious. At that instant, however, ballerinas might tell us they feel something like the fear of crashing. Yet we have seen gravity fail when people are plunged skyward.

– Emmanuel Iduma, in response to Kaitlyn Gilliland’s Workshop: Balanchine’s Serenade (2/27).