Our Own AIDS Time: Keith Hennessy and Ishmael Houston-Jones in Conversation

February 14, 2017

Originally commissioned by SFMOMA’s art and culture platform Open Space for Lost and Found: Bay Area Edition, curated by Open Space editor in chief Claudia La Rocco and inspired by Danspace Project’s Platform 2016: Lost & Found.

Ishmael Houston-Jones: I texted you that it was significant we were doing this on MLK Day and a few days before Trump’s inauguration. Somehow it adds a little bit more weight to what we’re talking about.

Keith Hennessy: Yeah. How does this day influence just even how you think about these things?

IHJ: In a certain way my art practice has always been tied up with my activist practice. I was never dealing solely with aesthetics. I was dealing with the socio-political world in which the work was being made. I just did this Lost and Found Platform at Danspace Project that looked at the AIDS crisis in the ’80s and ’90s and activism related to that, and how that has influenced dance work being made today… so I think, it makes sense that we would be talking about this today.

KH: Yeah. It’s interesting for me as part of the number of things that have happened in the last five years that are revisiting that particular AIDS time and also looking at the intensity of cultural production that was activist art and/or activist-motivated art practices, including our own. The Trump inauguration seems to be provoking, right from the get go, a lot of response, whether that’s activism or activist art or politically engaged art. Something’s turning and breaking but something is also going to be sustained. We can see into the future and go, “There’s a whole bunch of work that needs to be done and we’re going to be doing it for the next four to ten years.”

IHJ: That is my hope, yeah. I mean there was this moment around the election or afterwards when I just shut down. It was a common theme, people just feeling defeated and with the covers pulled over our heads. People are now engaging in many different ways, some of which are cultural and artistic.

KH: There’s a number of people in the Bay Area whose activism dates to the ’80s, ’90s ACT UP era. Do you know Anne-Christine d’Adesky?

IHJ: Of course.

KH: She’s part of convening this Bay Area queer anti-fascist network. Hundreds of people showed up at the first meeting. It happened within weeks of the Trump election; people are seriously organizing around a number of things — more recent activists and artists are involved, but in the core leadership are people who were in ACT UP in New York or San Francisco in the ’80s and ’90s. So again there’s some kind of circling around that seems potent.

IHJ: Yeah, there’s an intersectionality, people are seeing the connections between all of the oppressive issues. Probably in the ’80s and ’90s they were more single issue-oriented. A piece that I made in 1986, that was most directly referencing AIDS without actually referencing it was Prologue to the End of Everything, which I made after my trips to Nicaragua. It was a totally fictionalized piece about people dying in the streets and this Black American, being stuck in this country where people were just dropping dead. I didn’t even realize at the time, but when I revisited the text I saw that it was informed both by the government’s support of the Contras and involvement in Central America, and by the government’s slow response to the AIDS crisis.

KH: The pieces that I made, especially in the late ’80s and early ’90s are almost all either intersectional or you know, complicated. I’ve had an ambivalent relationship to whatever would be the center of gay identity and I’ve always operated more towards the edges of it. I think that’s because issues of anti-racism and feminism have always complicated how I would go to just a gay issue; even my very first piece that got a lot of attention, which was Saliva in 1988 and ’89, you look at the texts and there’s a little section on political prisoners in there —,really straight up, broad politics of a young anarchist, that don’t restrict themselves just to my own coming out issues, like gay oppression issue, and what that is in relation to the AIDS era and how many people had died by 1988 when I was finally making that solo. Before then I had been doing sort of hit-and-run solos but my focus wasn’t on solo work.

IHJ: I wish I had seen that work. I wish I had known you then actually.

KH: Well, I wish I had seen your work in the ’80s! My goodness. Ok one of Claudia’s questions is “How does the impact of HIV and AIDS continue to shape our aesthetics and politics?”

IHJ: For this Platform, I wanted to engage young, queer art makers, dance makers and just sort of see — I invited Will Rawls to co-curate with me because I was not involved with a younger generation of art making so much anymore. And also I was focusing on artists of color. Um, partly in response to the whitewashing in the museum exhibit, Art AIDS America. It’s much more complicated than it was in our day. That there is a layering of both aesthetics and politics and identity has been sort of shattered wide open. And I don’t know if that’s true of my work, I mean, I don’t know if my work feels like it’s of a different generation, which it is.

I’m sixty-five years old, I’ve been making work for several decades now and I hope my work continues to evolve but there is an aesthetic that I am committed to. It was interesting to see these younger, queer artists of color and how their work is different from mine: much more layered, much more complicated, both in terms of aesthetics and gender identity and racial identity, so many things that I personally wasn’t dealing with when I was their age.

KH: Yeah. There are changes in how everyone’s approaching gender identity; within queer circles, those of us who used to think, well, we know what our gender is and so that’s the end of the story, have been called to identify differently, to recognize that being cisgendered is something. I went to hear Tara Willis interviewing Dana Michel and Ni’Ja Whitson, and the opening question was, “How about just check in and tell us how you’re doing today and tell us your name and your gender identity?” And there was an opening five minutes of a conversation that was about Black arts, Black aesthetics —, three Black people on stage that identified within the female to trans spectrum —and the opening five minutes was casual but at the same time profound talk about gender identity. If someone was interviewing you and me, especially back in the day, we just wouldn’t have started with that. And we might not have ever even gotten to it. People would have clocked us as cisgender, we would have taken that as a norm and then not even mentioned it.

IHJ: Right, exactly.

KH: And that’s different from being men who understand, say, the importance of feminism. It’s more than that. And it’s an interesting difference, just in terms of what people are bringing to the work. But also AIDS changed a lot. One of the things that I’ve noticed is that it’s hard to talk about the time that we know as an AIDS time; I always hesitate to say, “Oh back during the AIDS pandemic,” or “back during the AIDS time,” because other people are living and have been living, since the mid ’90s, their own AIDS time, right? So then it’s like, what does it mean to be more specific about the AIDS time that we lived through, that AIDS time from say, the early ’80s to the mid ’90s, up until protease inhibitors were developed, and to recognize it as a particular era that is marked by the nation states that we lived in, the economic class politics of the nation states that we lived in, and the networks that we traveled in? That was an AIDS era in a particular group, Northern Hemispheric people with access to healthcare.

IHJ: In the Platform we dealt with the fifteen years from ’81 to ’96 specifically, and we kept having this problem that you’re talking about: how to name it. What to call those fifteen years, from the first New York Times mention of gay men dying of mysterious cancer to the protease inhibitors. What I also clocked when writing my intro to the Platform catalogue was that there’s a sizeable number of people from our generation that’s missing. There’s a missing link of queer artists, of queer elders. I am a survivor of that, but there’s also this whole bunch of, particularly men, but men and women, of that era who never made mature work. They never were able to mentor, to pass on their mistakes, wisdom, whatever. So many people in the arts — again, all communities, just we’re talking about the arts community — just disappeared. We were trying to interrogate what it means to the art that is being made now, people are repeating things that maybe would not have had to be repeated in a certain particular way.

KH: Have you ever been to the Jewish Museum that Daniel Libeskind designed in Berlin?

IHJ: No, no.

KH: So, one of the interesting things about that building that continues to have relevance in all kinds of areas is that there are sections of the building called the Voids, where there’s nothing there. I think about that in relation to the question that you’re asking. There’s clearly some histories lost, there’s some people who died very young, they were on a trajectory, that trajectory ended suddenly. There’s a whole future that didn’t happen because those people didn’t live another kind of life where they get to live longer. We could unpack some of that and learn some of it but there’s another section which is like, these are just the voids. We can’t even predict how history would be different, you know?

IHJ: Exactly.

KH: Sarah Schulman writes about how real estate changed in places like San Francisco and New York when that many people were dying. You have thousands of people die in one community within a ten-year period and that can shift the real estate of a neighborhood, of five neighborhoods. But at the same time, we can’t really predict what would have happened otherwise. It becomes this space that you can’t really see into, you can’t get clear shapes or information from. I think about that a lot when people try to put it together.

IHJ: It’s an unanswerable question. In my curatorial practice, that is what I like doing, to get in there and grapple with a question that I know is not answerable.

KH: The Lesbian/Gay History Society in San Francisco did an exhibit of dancers who died of AIDS. They were looking at West Coast, trying to find people who had not previously been historicized. I went to the exhibit with a number of other people and we started to gravitate towards each other — and when I say a couple other people, it was people who were here in the ’80s and early ’90s making dance works — and all of a sudden we looked at each other and we realized, the only reason we’re here is just because we lived. There wasn’t something more profound to be said. The people in the photos on the wall died and we didn’t and so now we’re standing looking at the pictures. And every now and then people would come up to us and be like, “Oh you’re here! It’d be so great to get your opinion on this, or that,” and even though we all have stories to tell it was just this very eerie thing of like, what does it mean to survive? It was quite destabilizing actually. I left there and I was like, I don’t even know what the purpose of this exhibit was; and it was quite broad, who was included. Like what a dance community is and linking LA to San Francisco, which is a big jump … one of the speakers was the mother of one of the people in the photographs and he had been a dancer in Madonna’s Truth or Dare tour and movie. We listened to her and it was compelling and at the same time it was like we were all speaking across some giant space that we couldn’t really see into, that we would sort of talk across. It was a trip.

IHJ: In 2010 when I reconstructed Them, a 1986 collaboration with writer Dennis Cooper and composer Chris Cochrane, so much of the rehearsal context was trying to communicate to dancers in their twenties what that time was like. Dennis’s text stayed largely the same, Chris augmented the music, but the dance is made by the dancers, their bodies. Even on an aesthetic level, dancers are different now, twenty-five years later. Their training is different and how they approach movement and how they approach their bodies and also the gender identity of the dancers; to have an all-male cast means something entirely different now than it did in 1986. But also trying to get them to understand this context of AIDS, what Chris and Dennis and I and the original dancers were living amongst, that was the main thrust of the rehearsal period.

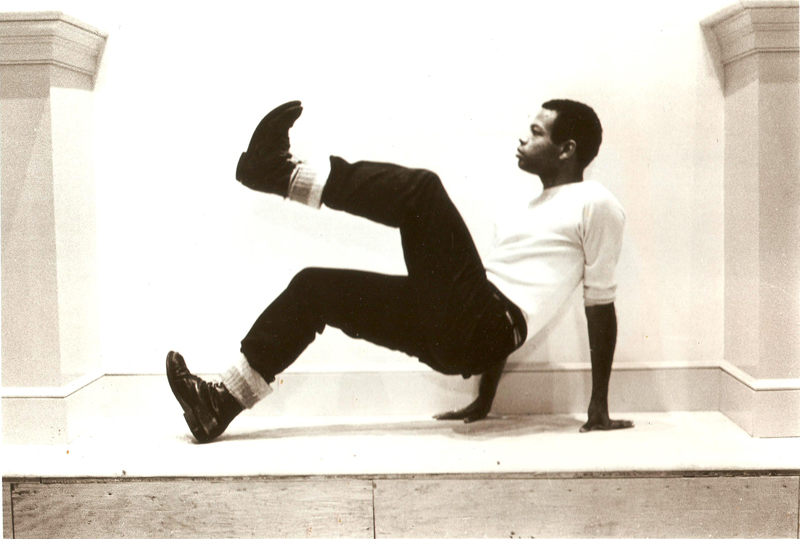

In the piece I did for this Platform with Miguel Gutierrez, we reimagined — which is a word that neither of us likes but we can’t think of a better word for it, because it wasn’t a revival and it wasn’t a reconstruction, it wasn’t our take on the choreography of John Bernd, who died in 1988. I had danced in three of his works. He was a very important figure, he was the first Downtown, East Village dance person who most of us knew, who contracted AIDS before AIDS was named, before HIV was named. He had GRID … and he died at age thirty-five. The piece we made, Variations on Themes from Lost and Found: Scenes from a Life and other works by John Bernd, is sort of a fantasia about what his work could have meant, what could have happened to it, and what did happen. Looking at videotapes and dealing with my memory and the memory of some of the dancers of that time and trying to work with that as material was difficult. It was difficult emotionally and it was difficult artistically too. We pulled it off as best as we could, it got generally positive responses from audiences, the dancers I think all felt really good about it, but it was a really difficult process actually.

From Variations on Themes from Lost & Found: Scenes from a Life and other works by John Bernd. Photo: Ian Douglas.

KH: I wish I had seen it. Miguel did a little bit of writing about the project when he would send out an e-blast and it was clear that he was being deeply affected by the process in ways that he hadn’t expected. When you came together he thought, “Oh, I’m going to learn about this artist and I’m going to help restage this work” but instead it became a larger confrontation with himself and who he is and who he is with you and other people.

IHJ: It was so much more profound than either of us thought it was going to be.

KH: For a number of years, I’ve been doing this workshop in death and dying practices. One of the first things that I do, as a kind of warm-up to start the day, is I have everyone dance the hustle. They all get really into it and I make a joke that I’m teaching one of the ritual dances of my people. So they’re expecting some kind of pagan or folk dance. And then once everyone has learned it, and we’re all having a lot of fun, dancing to the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack I say, “Now try to imagine that disco was a big part of my life, try to imagine that the people that I was dancing with in bars in San Francisco in the early ’80s, that anywhere from a third to a half of them died.” And so this is also a ghost dance, it has all kinds of weird memories for me. The gravity of the situation shifts and we redance it, now thinking, “Ok, what is it to use this as some kind of ancestor dance?” The disco dance as an ancestor dance. And they can call in their own people, their own dance teachers and histories and stuff like that. I think I first did Body Electric stuff in 1988, and very soon into the Body Electric work, which was focused on sexual healing, people realized that there also had to be work done around death and dying, that that was one of the most important needs in the community. There was this whole practice that was developed, that at the time was called Midwife to the Dying, and it was seen as this particular role that gay people and our supporters and allies could play. It’s again, something that deeply affected me then, it set me up for the kind of work that I’m doing now, fifteen and twenty and twenty-five years later, that’s still rooted in that time. Thinking about death and dying, thinking about how the culture around AIDS challenged all kinds of things — what does it mean to die, how to die, what are bodies in death, who takes care of bodies, what happens when the bodies are some kind of abject object to society, and so then the community has to figure out its own new approach to death and dying, and also just the class war that is death and dying, what does it mean to rethink burial and the costs of death and who does what, who washes a body? There’s been a lot of communities that have influenced the shift in American approaches to death and dying, but a giant step was made as a cultural move through the response to AIDS, and it’s still in my work. I’m still doing it, I’m still developing it, I’m still evolving it.

IHJ: You probably know this already but I recently found this zine that I helped put together in 1998, ten years after John Bernd died: me, Jennifer Monson, Lucy Sexton, and a whole range of people who had been in John’s care group, we had a dinner and we put together this photocopied zine of ephemera and things we wrote. We were either in our late twenties or early thirties then, and to read that a couple of decades later, it’s really profound. One of the essays that was most effective to me was by this guy Michael Spiller, a lighting designer who was like twenty-five and was the choreographer Yvonne Meier’s boyfriend and he just sort of got roped into helping. He wasn’t really close to John but he wound up being sort of his social worker. He was acting on political beliefs, he was going to help him get on the rolls of Social Security and disability and stuff. He was at first saying that he thought his role was just political and really just helping with logistics, but he later felt that he was changed forever by having gone through this. People in their twenties and thirties are not prepared; there’s nothing that prepares you for a mass death, the death of so many people you know personally. There’s nothing that can prepare you for that. I’ve been thinking about that a lot, in terms of how it influenced my work; I can’t put a name to it, or say, “In that piece, that was that.” But I know I did a lot of pieces that referenced death and dying. I actually joked that my titles at the time were Dead, The Undead, Without Hope. It affected me, but I don’t know how it affects me now. I know there is something from that time that will never leave me. And now that I’m the age I am now, in this “natural progression” of things, friends of mine are dying again. On one level I feel more prepared, if one can be more prepared for that, and on another level, I just feel like I don’t want to go through it again. My friend, Fred Holland, died this time last year and several of the same people — Lucy, Johnny Walker, Michael, Yvonne — were all around again and we were going, “Uh oh, it’s happening again.”

KH: Most of us did not grow up in a situation where there were care groups around the dying. It was restricted to family. But then during the AIDS time, many of us were in care groups. I think about Remy Charlip dying twenty-five years later or however long, and how organic it was for a group of us to make a care group. It wasn’t an only gay men’s group, but it was a pretty queer group and it was mostly gay men and his best women friends — so again, a sort of classic dancer profile. Women and gay men. I just think about how simple it seemed to be: “Oh, Remy’s had a stroke, we need to set a care circle.” That’s a cultural form that people could have developed in many different contexts but most of us, the first time we ever did that was during those fifteen years when AIDS was heavily impacting gay male cultures in the US. Among others, but that’s where our entry to it was. We could also just refer to it as it impacted the dance world.

IHJ: Right. I just realized now as we were speaking that last winter when Fred had cancer, just colon — just colon cancer, as though that’s trivial — but he had colon cancer and it kept reoccurring and then it would go into remission and the last bout was really, really vicious. A lot of the same people — Lucy Sexton, Jeannie Hutchins — were the same people who were around John. There was a reoccurrence of the same constellation of people, who were visiting Fred those many years later. And it was that preparation I guess, that training, that made it really normal and natural that we would do this. Spend nights with him in the hospice, just feeding him. We knew that. It was kind of horrible. Also, you know, he didn’t have family here except for his 24-year-old nephew who flew in from Denver and was fantastic. I mean Fred was a straight man who was a dancer, who was an artist, who didn’t have family nearby. And people rallied. We made the memorial service, and his family did fly in from various parts of the country. His brother Aaron wrote to me a couple of weeks later, a thank you note saying, “We always thought that Fred moved to New York and was all alone, we were sort of shocked that there was a church full of people, overflowing.” The blood family’s impression, and I think this is for a lot of us, is that we’d moved away and we were these lonely artists living these solitary lives.

KH: I think a lot of people don’t really understand the family of choice, the family that’s community-based, the family that’s built around our work as artists, because it’s also not like a normal work community either. We have a different kind of intimacy that’s built into the work, right? It’s very bodily, so it’s not as strange for dancers to imagine being involved in the life of a deteriorating body or for non-family members to participate in this intimate work of feeding and caring for, even just doing the laundry of someone who’s dying. And how it’s different from doing the laundry for someone who broke their leg and is going to be fine in a month.

IHJ: What else did Claudia ask?

KH: “Can you talk about your relationship to activism, whether in your work or beyond.” That’s a very short answer in that I have never really separated artistic practice from activist work. I can see the difference between, say a protest, and a performance that starts at eight o’clock but my work has always been talking to and talking with and talking from the social movements of the era that the work is being made in. I have some long-term concerns and issues; I look at things like my participation in what now can be seen as the prison abolition movement, support for political prisoners through a critique of the prison industrial complex to where we are now, that’s been in my work since my first solo piece and maybe even some of the earlier group works before then. I’ve never not had the work be talking to activist concerns and social movements, even though I’ve protected a certain experimental space, where I don’t just have to do party politics art.

IHJ: My work comes out of my biography, who I am and what my concerns are in the context of the real world. That always is where the works are starting, with my body and that context, in that world, in that time space. I wouldn’t even know how to separate my activism from my aesthetics. I know I have a very sharp critique of work that somehow poses itself as political work, and I sort of hate that term… I remember when we were working on Them in the ’80s,we definitely didn’t want to make a “AIDS piece.” Because… those quotes, those implied quotes, drive all of the queer out of it and all of the juice and all of the truth out of it. Actually Them got slammed by the gay press when it came out, they were incredibly hostile to it, for understandable reasons, because it wasn’t a “Gay Piece.” It was a piece that talked about queerness in a way that was threatening. One of my favorite quotes from the New York Native, which was the gay weekly at the time, was, “These homosexuals are anything but gay.” I always wanted to get a t-shirt that said that. So I do have a critique of work that is party line agitprop work; I am an artist, I do have aesthetic concerns as well as socio-political concerns, they’re tied up together very tightly. I can critique people’s politics and I can critique people’s aesthetics. I can definitely critique my own.

KH: Coming from San Francisco, I think we draw the line in general a little differently than, say, a New York artist. That might even be a difference between your work and my work; I have foregrounded many times in my life, being a political artist who made a political piece, not to everyone’s acclaim for sure… even when we start to separate and go, “I have aesthetic concerns” and “I have socio-political concerns, I’m also very interested in the politics of experimental art. There’s a potential to some of the experimental work — and I’m just using that in a large way to separate it from say, a social justice narrative piece, or a party line political piece where you’re presenting solution-oriented politics or propagandistic performances. I’ve always liked the pieces, in my own history, where you go from propaganda to being lost and not knowing exactly what’s going on to something that you do understand. I have always made complex pieces where the propaganda can only be one aspect of it and others had to be working through issues from a place of not knowing or from mystery or from some sense of ritual, or some kind of formal experimentation, where I’m just going to deconstruct something or be minimalist about an action so that I can learn something different about it. And I think that there’s real social change potential in these tactics that are often misunderstood by the people who foreground propaganda politics or a very small idea of movement politics.

IHJ: That’s actually a much better way of saying it, propaganda politics, propaganda pieces. I remember I did feel and I probably do feel still that something as simple as Contact Improvisation had huge political ramifications in the way people experienced dance. Both in terms of an egalitarianism, a supposed egalitarianism, and supposedly dissolving gender roles.

KH: At least the basic proposition of the dance is not gendered, so whether that succeeds or fails is already really radical, right? The dance proposes that it’s not a dance to music, which separates it from a lot of kinds of culture. Some might affirm that that makes it even whiter but in some ways that also pulls it out of the whole set of historical connections. But then it proposes, anyone dance with anybody and there’s no role prescribed for any one body, not by age, not by gender, not by amount of experience.

IHJ: I remember that was a big political awakening for me. Finding Contact Improv. I’ve been showing in my classes the piece that Fred Holland and I made in 1983, on the tenth anniversary of Contact, where we did everything wrong. The first wrong thing in our manifesto was that we were Black, and that we’d used a loud sound score, and we wore boots, and clothes, and we talked and we stayed out of physical contact as much as possible. It was a re-radicalizing of the Contact trope.

KH: I really wish I had seen it.

IHJ: It’s actually quite amazing.

KH: Although I’m glad I didn’t see that link say four months ago because then I would have had to put it in my dissertation and … I really had to stop writing and thinking about anything. Did you know that I finished?

IHJ: You finished?

KH: I fucking finished.

IHJ: You’re a doctor?

KH: I’m a doctor. With a dissertation on the ambivalent politics of Contact Improvisation.

IHJ: Wow.

KH: A large part of it is actually thinking through these things that we’re saying. Like, here’s the potential, what I call the radical potential of this experimental dance form, and then where did it default — especially as it developed —along lines of whiteness or gender normativity or even neoliberal economic politics. Like the movement from collectives and jams to individual teachers and global festivals, you know, like Contact as a retreat space as opposed to an ongoing practice. All these different things I tried to look at.

IHJ: Cool. It’s great talking to you. I’m so sorry I wasn’t around last week.

KH: Yeah, cause I was definitely prioritizing hanging out.